Shelan Holden, Sociology, Lancaster University (2021 Cohort)

My research is on the impact that the 1984/85 miners’ strike had on children and young people at the time in a former mining village in South Yorkshire. This has involved a lot of travelling from Lancaster to Yorkshire, for both archive and interview work. Because I am disabled there was no way I could make that journey every day, and my ethnographic fieldwork relied on me immersing myself for stretches of time in the area. Throughout my studies, and more so since conducting my research, I have found the RTSG support funds crucial in me being able to conduct my research so thoroughly.

I resonated with Miriam Tenquist’s post in the NWSSDTP newsletter (June 2023) on cultural sensitivity, adaptability and respect, as her words mirrored my own experiences, inspiring me to reflect on this under researched part of fieldwork. The importance towards personal cultural awareness is often lacking in textbooks or articles and are conveyed eloquently when Miriam notes ‘’ I made a conscious effort to familiarise myself with Chinese cultural practices, which not only enhanced my interactions but also created a safe and comfortable environment for participants to share their stories openly’’. This cultural respect is something I have found very important in my own research. The emphasis in the qualitative interview is on the ability to acknowledge that, as part of this process, the interviewer and his or her behaviour are also interpreted by the participant (Rubin and Rubin 1995, p. 39).

Former mining towns and mining communities are notoriously challenging to engage with, there is a deep distrust of the media (as a direct result of the way the strike was portrayed by the media at the time) and of anyone outside of the community. There is good reason for this, coal mining by its very nature relied on a strong supportive workforce and community, which produced an insular way of living that was vital (in times of both crisis and the everyday). My research is already highlighting how the rhythms of the pit dictated how the community experienced their village affectively : hearing the nonstop machinery, the siren that highlighted the start of the shifts (if that siren went off in-between then it meant there had been a disaster), seeing the headgear on the landscape as the children grew up, the smells of the vibrant market place on a Saturday, tasting the coal dust in the air. Because of this, I knew that some of the stories shared in my research would be the first time many participants had a chance to discuss an event that occurred over 40 years ago, and that there might be an emotional cost to them. I also recognised that many of the miners would be aged 60 and above, so extra care was required in locating the space and place of the interviews. Herzog (2005) suggests Interviews dealing with highly emotional, sensitive or private issues, are best conducted in the home of the participant since such a setting offers a sense of intimacy and friendliness.

To this end, I decided on a range of accessible interview spaces, to suit participants and enable them choice, (in where they wanted to be interviewed) and gaining trust from former mining communities was key. I arranged an informal launch in the local working men’s club, advertised via different media, and ensured I had a safe space to conduct interviews in a wide range of accessible community settings or in their home. As Miriam highlights, this building of trust comes with a recognition of cultural values and etiquette, and never more so than when entering people’s homes. As Hana Herzog states Interviews not only construct individual subjectivity but also broaden and deepen the concept of knowledge and its sources, incorporating the subjects’ experiential truths into the process of the creation of knowledge (2005:26)

So, how to acknowledge and capture this without taking away the participants voices, to show that I had respect, to build rapport trust and crucially for them to feel they had power and agency in their words and How I would use them? This is the point where research and an understanding of cultural practices is important.

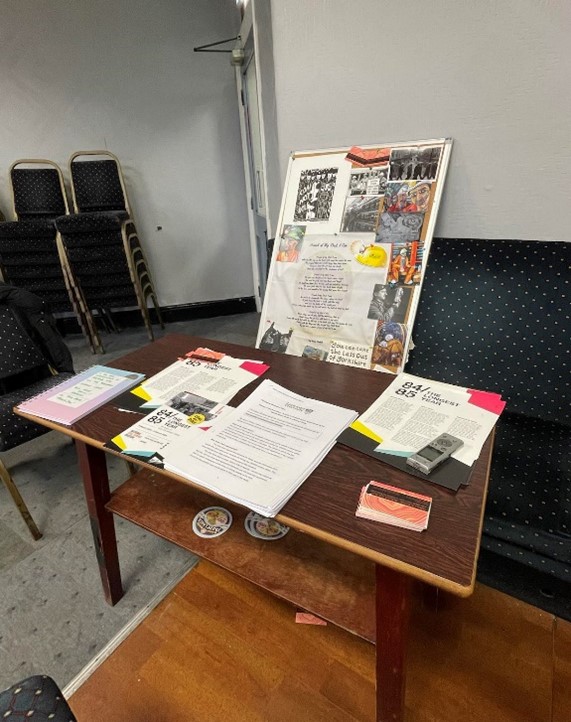

The culture of a community is significant, and some of the cultural rules in coal mining communities, are crucial to appreciate. For example, when entering someone’s house: Take your shoes off, (or offer to), bring a gift, be prepared to be asked directly about your links to the village. I made sure that I came bearing a participation pack, (Figures 1 & 2) which was given to all participants as well as at the launch event. This included printed off information on the project (a copy of the consent form and participant information sheet) along with leaflets about the strike, poetry and information on the NCMM (National Coal Mining Museum). The biscuits I brought to home visits were from the museum (although I was also keenly aware that for older generations the aspect of ‘the funeral biscuit’ might be an issue so I brought cake!) to promote the mining museum and to highlight its ongoing community sessions. This prompted community leaders to offer free items, the curator of the museum gave me a selection of old stock for free, which included pens and stickers and the town council gave me free booklets on the history of the village. These gifts were accepted by participants with ‘oh you shouldn’t have but they do look lovely!’ quickly followed by ‘so are you from round here then?’. My reflective journal notes how the politics of being local and the power dynamics of gift giving will be explored further as I start to write my chapters.

Overall, as I come to the end of my fieldwork is that this experience has given me a renewed admiration for coal mining communities: their stories, their humour, and their generosity. I hope I have conveyed here that the art of interviewing often involves the art of giving, and that by respecting communities, especially older communities, a simple packet of biscuits and a smile can bring an equal amount of respect. I want to highlight here the vital way in which the funding has supported me in gaining this valuable data.

References

Herzog, H (2005) On Home Turf : interview location and its Social meaning. Qualitative Sociology, Vol. 28, No. 1, Spring 2005

Tenquist, M (2023) The Journey of Fieldwork: Unravelling Stories of the Older Chinese Community in the UK Posted on June 20, 2023 https://nwssdtp.ac.uk/2023/06/20/the-journey-of-fieldwork-unravelling-stories-of-the-older-chinese-community-in-the-uk/

North West Social Science Doctoral Training Partnership

North West Social Science Doctoral Training Partnership